Collapsing Now, Gone in 2030

A guide to how it's worse than you think. Full bibliography of 270 peer-reviewed publications or government alerts: https://archive.org/details/collapsing-now-300-documents-theory

I think I can explain why most things keep getting worse. I think there’s an explanation for why the IPCC and COP have been doing their things for so many years and yet CO2 growth keeps accelerating. It’s the same reason governments are more populist and we’re all getting sicker, and why we have more wars, hunger, inflation and movie sequels than just a few years ago. I think we can even explain why global overshoot ever got as bad as it has, and the worst thing is that as complicated as these problems are – the driving force might be quite simple.

It appears as if there’s a problem in humanity. Specifically, in our minds. And unfortunately until you look at enough datapoints, it’s not going to be clear to you. Because you’re not looking wide enough.

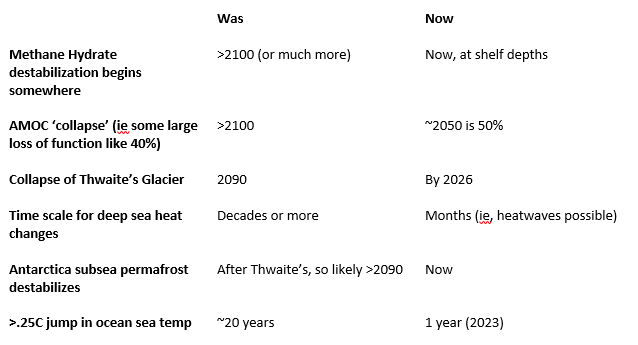

Let me show you something:

What do you see when you look at this? Six updated predictions yes, all that have moved within the last 4 years. Is this just a display of increased ocean heating? Maybe surface waters jumping up? Well that can’t be it alone, as some items like the AMOC and hydrates are more about heat distribution than heat itself, and Thwaite’s is at least partially on land.

I think what’s most eye-catching to me about these items isn’t that they’re about heat, or that they’re updated, but that they’re all updated in the same direction.

It appears in each instance a prediction has been made for a system and when that system might shift to a new state, and in each one of these cases that update has been towards ‘more of a danger.’

I think I can prove to you this isn’t random. Something is going on here, and it directly relates to the state of the world.

Big picture: What sits before you now is a lone researcher’s project on how a pervasive conservative bias has spread throughout the world we’ve built in such a way that the true size of ecological overshoot has been hidden from us all. My plan is to give you tools to spot this bias, for us to attempt to correct for it, and when we do I’m afraid that I’m also going to have to show you a general collapse of the Earth system, just sitting there right in data already published.

This is a system review of as much of Earth as I can, or maybe an expansion to Limits to Growth from data, made because no one is paying to do these things anymore. In practice our synthesis is going to show events we once thought were far into the future are not. They are in fact often happening right now. Deep ocean heatwaves, methane hydrates disassociating, major governments falling, all are current events and there’s a clear reason why.

We’ll go over this in detail, and I show you both method and application of theory, so that you can scorecard and determine for yourself.

But first some notes –

-The datapoints we are going to use in this project are all peer-reviewed, from primary researchers, or from government agencies. There will be a few NGOs, but only very few. The reason there are so many? It’s not until the scale becomes obvious that the magnitude also comes into focus.

-There is no new research here, and I claim no ‘special’ knowledge. I have no agenda and will leave no contact info. No patreon, no nothing. This is just a theory, shared freely.

-This synthesis is not linear, and feel free to skip around. I am deliberately informal, and trying to make the material accessible. Jump wherever you want. Use the simple table of contents. Go back to things and go to the support documents constantly. I have only highlighted the very most obvious connections for you, but rest assured there are many more. Go looking.

-I do not refute the scientific process or climate change, or even focus on only climate change. We will cover all sorts of systems and their interactions, but we will also go multi-domain.

-Yes, we will absolutely be talking about societal collapse but only when it becomes the obvious conclusion of the bias in action. Time and again it’s going to show up, and that’s really not my fault. I’m using numbers provided by the IPCC, or the WWF, or James Hansen, and if you think there’s cherry-picking your beef will need to be with them. Full papers are included.

Finally, let me admit now I have no solutions for you and that some of this material will be emotionally difficult. It has to be, that’s why the bias exists. Unfortunately, it seems the human race has sleepwalked right into an apocalypse, and all I can do now is show it to you. In existing data.

Shall we begin?

A heuristics approach

I understand completely how big it is to claim a connection between so many events and THEN also state an (ongoing) collapse. I’m not being hyperbolic either – which means something pretty big must be going on right?

Simply put I am going to define conservative bias here as a tendency for humans to assume values for the unknown, and rather than place that value somewhere random, put it instead where it is more safe and nonthreatening.

My theory is that the reason all the examples in the table got revised in the same direction (faster than expected) is because most of our conservative bias manifests in the same way. We humans like to put theoretical danger further away than it really is. And we do this…everywhere, all the time, and I think you might be aware of it in your own life but maybe don’t assess just how much you do it.

And since this problem is likely a biological quirk of our species (which is why it’s everywhere, not just one or two cultures), I assert it is more prevalent (widespread) and powerful (magnitude) than is generally recognized. And btw, I make no claims about the historical nature of this bias. The datapoints we’re using really only go back to 1970 or so, and so we’re going to focus just on the modern world.

So what is this conservative bias? Where is it, how does it hide, and how do we assess it?

I have a simple relationship equation for you:

(assumptions) + (application) + (synthesis) = (conclusions)

This is our core of empirical science, our nice little model to get some work done. But here’s another way to consider this equation:

(wrong assumptions) + (wrong application) + (wrong synthesis) = (size of possible error)

In this version we see that one error, put up with an error, starts to grow error at the other side of the equation.

In the same way I assert conservative bias exists in two primary forms that are compounding together:

1 Inside of a domain – this would be when someone makes a bad prediction on aerosol forcing, and then climatologists go along with that number

2 Outside of a domain – this is multi-domain synthesis, when no one even bothers to add up microplastics + pfos + nitrates acting together

Ok, great, so there’s a potential for error to build up in a system. We understand that, but how do we spot it? And how does this lead to a global problem?

I have thought about at different points putting together a theoretical exploration of bias in the individual, in the institution, and in society here. I also considered formalizing how to measure bias in each of its two forms, an equation to constrain the magnitude of bias sort of thing. But I’ve decided against all that.

Why?

Because this isn’t a formal publication, and because I think if I tried to do that, it would take too much time. And worse, it would silo this work more. Make it less approachable.

And I truly mean it when I say I think we all don’t have much time left, and that everyone everywhere should be given a chance to see what we’ve done.

So here’s what we’re going to do:

We’re going to fix science (because it is the best tool we have, it just needs calibration) in a quick and easy way, and then we’re going to take this fix and turn around and immediately look at the data, and you can start seeing if I’m right or not. We’re going to correct for this bias I’m claiming, and see if the correction makes things a bit more obvious for all of us.

Rather than something complicated and formal then, we’re going to need something fast and memorable that we can keep referring to – a heuristic.

A heuristic is a sort of verbal algorithm, not as formal as an equation but better than just a general phrase like its worse than you think, or faster than expected.

At the root of this entire document is a fear from the author that everyone else isn’t afraid enough. That the human race is so avoidant of fear (or perhaps attracted to safety) that we have pushed it away when it should be closer. That we’re refusing to admit our ignorance.

So that’s a good place to start. It also happens to be the foundation of empirical science.

1 Admit Radical Ignorance

If there’s a problem here to solve, our investigation begins with us admitting that nobody really knows anything firmly. Science is all about figuring out, and so let’s acknowledge that. Before anything else from me, let’s just acknowledge we need to question everything. Question the documents I give you, question my theory, question my interpretation, question me, but also remember you should question everything else too.

Our next step then is to start addressing my fears, my conservative bias theory. How do we go look for it? Let’s start by assuming it’s there at all, and that it’s big, and then we can see if it really does show up or if we’re holding nothing by the end.

2 Acknowledge sometimes humans might be using answers we want

This conservative bias is all about fat-tail risk. It’s about the idea that people might be putting events further away from them than reality, just like in the table at the beginning. I’m not saying they’re making intentional errors exactly, but just that institutions, societies, disciplines all have the potential for bias.

Imagine for a moment a radiologist sees something bad on a daily review of scans. He’s going to use language to describe it to a GP, and then that doctor will have to tell the patient. And then the patient has to tell his child. But now imagine that at every stage of that chain, the language that is used gets softer. Gentler. More kind.

That’s the conservative bias inside a domain – we didn’t have to get anyone else involved, but at every point in our own chain we maybe altered the data a bit.

But we’ve got that other form of the bias I mentioned too right?

Let me ask, do you think in general there is a connection between general amounts of chemical pollution in the world and disease rates in the human race? Thalidomide causes birth defects, and the more Thalidomide there was the more birth defects there were in the community, so yes, right? But can you find any studies that just map ‘here’s how many chemicals a country produces’ vs ‘here’s how much general sickness that country has’. Just a very general chemicals produced vs diseases in action. I can’t find anything like this, and yet it’s just so obvious.

Likewise, remember our table at the beginning, and how everyone was wrong in the same direction? Have you considered that everyone had to move faster because of a single factor (say a rise in earth’s energy imbalance)? Or what if that isn’t the case, and instead…the guy calculating ice loss in Antarctica suddenly has to account for each of weaker currents, Thwaite’s buckling, and heatwaves under the sea ice. All at once this guy has to become a master in multiple physical domains just to make sense of what he’s seeing.

This is multi-domain study and it’s something we do (as we’ll see) little of in the modern world. Organizations like NOAA and the IPCC are famous for doing these, but they do seem to be getting less funding these days…Do you think that might be a problem?

3 Look up (ie, what does this mean for everything else?)

We’re going to do a lot of systems level reviews of things in this piece, entirely because no one else is, and this is where the third part of heuristic comes into place. This is the conservative bias where instead of making errors about the little things, we don’t even bother to do a synthesis at all. It’s just unknown.

Do you think nanoplastic particles building up in brains could contribute to a rise in populism? Nanoplastic particles do cause inflammation in some tissues, and brain inflammation does cause erratic behavior. Could that be a contributing factor? Probably not right?

But how do we say that with any confidence? That’s a conservative bias and the worse part is, here we just make an assumption because no one is studying it at all.

So here we have 3 quick heuristics I’d like us to use when we go look at some data.

1 Admit Radical Ignorance

2 Acknowledge sometimes humans might be using answers we want

3 Look up (ie, what does this mean for everything else?)

In practice these heuristics are going to be a lot like ‘keep an open mind’, but more specific. We’ve got a process here. First we realize we can question everything (especially ourselves and our assumptions). Then we ask hey, is there some value here we might just be assuming wrong? And then finally we look up and we ask, what does this mean for global warming? Or for failing nations? Or for the Limits to Growth?

And that’s it. Now let me show you what doing this reveals…

Atmosphere & Solar

EEI

(note: Here’s what we’re going to do now. I’m going to go through the domains as listed in the support documents, and speak to what I see. But this isn’t going to be a deep dive or a walk-through of each subject. This is going to be pattern recognition. Be warned I will jump around a lot. I will ruminate and ask questions without answers – and that’s the point. I said this problem was everywhere so we’re going to go wide to assess it. Go at your pace. You have the data now; you have the heuristics. Apply them with me, and ask, is there a pattern here? It’s not about individual claims, it’s about why are there SO MANY examples of observations proving to be worse than our predictions or models? Pretend I’m with you, speaking to you if it helps, but I will not be explaining each detail or labeling every citation. You will need to do your homework to keep up.)

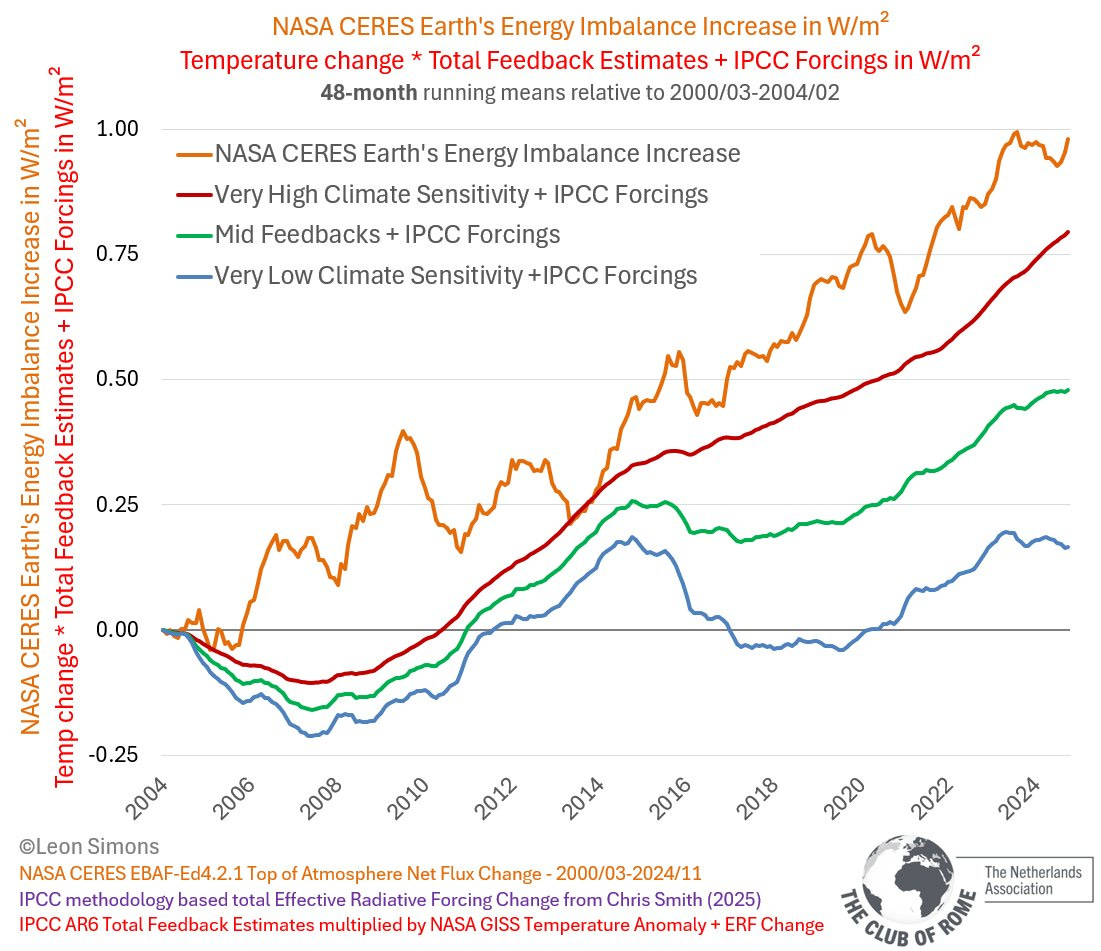

Earth’s energy balance has increased at something like .45w/m2 per decade for at least 2 decades. The EEI represents the amount of solar energy into the earth system, versus the energy we bounce back out of it, and as Earth’s albedo drops more energy will enter our atmosphere. This leads to a feedback loop as melted ice means less albedo, less clouds (of the right type) means less albedo, and even darker oceans due to worse mixing means, you got it, less albedo.

Heat in other words, often makes more of the conditions that will add more heat to earth.

This is bad enough - but what if I also pointed out that while this general framework has been understood for some time, for 20 years now ever major institution has been measuring this amount wrong. Either that, or just assuming it’s value wrong without measurement.

And it looks like we’ve miscalculated by quite a lot.

(Leon Simons, https://x.com/LeonSimons8

note: all other references images can be found at https://archive.org/details/collapsing-now-300-documents-theory)

The IPCC AR6 had some estimations of EEI and possible earth climate sensitivities (ECS) they’ve been using for a long time, and CERES now shows we’ve tracked above all of these for the entire time (well, excluding one brief year – 2014). Or particular note here though, not only have we been above all possible pathways the IPCC considered, but the one they really used for most scenarios was the green line. This means all the majority of IPCC pathway scenarios are based on wrong assumptions, and always have been. So IPCC pathways, the 1.5C and 2C predictions as example, are based on a cooler planet than ours. Let that sink in – EEI is the literal base force that is causing our planet to heat and the IPCC hasn’t had that base driver right, or even close to right, for 20 years.

So wrong measurement, wrong assumption, lasting for the entire time of policy, right out of the gate. Please go look it up yourself and then we’ll resume our bias hunt.

Good? Ok, let’s go.

So all the IPCC predictions made on heating have been at least partially wrong. But that’s just one organization right? Sure it’s the primary multi-domain international one, but just one. Does this matter? It does when they’re the yardstick unfortunately.

Follow this logic – so far in the 21st century we humans have been pretty good at anticipating historical temperature changes. Seriously, until 2023 at least a year hasn’t come along where our predictions were completely off, and usually we can get it right down to hundredths accuracy.

EXCEPT now we know that when the IPCC was doing its predictions, or anyone else using their numbers, we had one of our basic numbers in the equation wrong.

So how were our predictions turning out correct?

I see some primary causes here. More than just one of our numbers in temperature calculation is likely wrong (more than just the EEI), AND until 2023 most of the numbers we’ve been dealing with were small, so errors were a lot easier to hide.

On the first point, if our heating forcing is wrong but our temperature predictions were right, we had to be wrong somewhere else in a way that ‘balanced’ out the wrong forcing. Hansen believes our understanding of aerosols was also wrong (atmosphere/Global Warming Has Accelerated), so that they generally cooled more than the IPCC assumed and that his bigger cooling then cancelled out the bigger heating to produce the number we use today. And that this balanced error worked fine until 2023, when SO2 aerosols were removed from shipping and whoops, we found out what’s really going on.

The second point is simply, when the temperature change was something like .11c/decade, nobody was quibbling over a prediction that was .01c off. That’s surely within natural variability yes? It’s only when systems start to accelerate away from the baseline that variance really grows.

BTW, I might accusingly point out that if we understood the system at scale, we shouldn’t have errors of any magnitude. And that every time an error DID show up, we should have worked damn hard to find out why. (Heuristic 1 and 2)

Regardless we are where we are now.

So what next? Well that EEI number is large, and it represents a lot of energy into the system. And we’ve only noticed the size of our error since 2024. So we need to do some catching up at the very base of the global warming tree (which means updating everything else).

I do hope Hansen is right. I am not sure that it’s entirely the case, but if it’s as easy a balance as lifting aerosol forcings up to match this increased heating than that’d definitely make the math easier. But I distrust what’s easy, and I think on what else we may have missed with heating that much stronger. Maybe our measurements of albedo are wrong – just like the satellite data itself might still be. I mean we were using one figure for 20 years that was wrong, yes?

What about how we calculate EEI at all? Generally we do it in w/m2, but have you thought about that? We’re partitioning the earth into little blocks in that calculation, and then trying to generalize a value of energy equal to each one of those patches. And sure, aerosols balanced out the heat before, but what happened in regions without aerosols? Sub 40S in the southern hemisphere there are very little aerosols, and so the waters there have had more heat on them for decades then assumed. Would that throw off our calculations of ice loss? Could we have been losing more ice than calculated from just this error?

Aerosols don’t cover everything evenly, and so if our math is wrong on the EEI that would mean we can’t ‘average’ it out so easily. Some places with aerosols would get especially strong cooling, and the places without would be much much hotter. What happens if we assumed that the amazon rainforest was getting less sun than it really was? Maybe we think the forest is more resilient than it is. Likewise, maybe we think Europe or China or India are actually LESS susceptible to heating than they are due to strong aerosols?

We get an uneven picture from this answer and that is if the answer is the whole picture. Again we are wrong.

This is the third heuristic in action. We were wrong, we did a bunch of wrong calculations, and now we’ve let those wrong calculations give us perhaps a wrong systems picture.

Aerosols themselves

No one knows how powerful aerosol effects are in climate change. Yes, we just spoke about SO2, but here we’re talking about all ‘aerosols’, or even just ‘tiny particles added to the air’. How many of these particles are there? What are they all like? We don’t know. We don’t know at what height, from what angle, in what situation, and so we create bell curves to ‘normalize’ all possibilities.

(atmosphere/ IPCC_AR6_WGI_Figure_7_6.png & aerosol measurements are good here)

The above is the IPCC AR6 estimation, but Hansen and Simmons contend that this is an underestimation. Specifically, they point to the reduction of SO2 in shipping fuels (2020 in north pacific, 2025 in the Mediterranean) as an example of the aerosol cooling effect being stronger than generally assumed. This is another way of looking at the EEI we assessed, but notice here it’s a ‘combined’ forcing, so when SO2 is a bigger value, all aerosols go up. But what if some of those other particles (and there are thousands) are ALSO different than we expect? Bigger, smaller, and all of them changing the general balance in subtle ways?

Of particular interest in assessing this possibility is how SO2 clears from the atmosphere inside of weeks at most, and sulfates by 22 months or so. These are general values and we can doubt them, but let’s use them for a moment.

The timeline for a burst in heating in earth’s oceans that started in 2023 and the reduction of SO2 in shipping fuels at the end of 2020 does partially fit then, right? But only partially in my eyes. As example while the EEI anomaly does grow suddenly in 2020, the reduction in shipping aerosols was only in the North Hemisphere and then mostly in the Pacific, so regional. Additionally, sulfates generally take at MOST 22 months to clear, meaning that the heating that resulted from their reduction should have been started showing up well before their full reduction. Similarly, if the aerosol reduction was the primary driver of heating in 2023, then the EEI increase which drove that heat should actually have appeared even before that.

But do we see it?

(atmosphere/Global SO2 & ASR.png)

There are definitely some signs of it certainly, and definitely in the region as a whole we get strong signal. Still ocean temps themselves only ‘explode’ in 2023, not along with the EEI. This makes me suspicious that the heating burst is ONLY aerosols. In fact I might go so far as to say my suspicion is that aerosols might be the single biggest component, but are small compared to the pure amount of forcings that likely have been in the waters both prior and post the 2023 burst. But we’ll get to that.

(atmosphere/Aerosol forcing by year.jpg)

When we investigate 2023 and 2024 I always like to play, what else could explain what we see? Could other aerosols be at play? Maybe there’s something that we’re not tracking, or more aerosols of a different type that do something else? We’re already looking at one aerosol factors here, why not consider the rest?

(atmosphere/ EEI 48 month.jpg & NPA EEI2.jpg)

And what do you make of overall EEI estimates in light of this? Because here in the 48 month running mean we see no signs of a pulse at all, even though by 2025 we should have 3 years of it. And even as the EEI in the pacific was driven more by falls in the PDO than by anything else?

I don’t bring these up for any particular conclusion yet, just to give you a sense that trying to figure out something like air temps is going to involve ocean temps, aerosols, and sun estimation at minimum. And we really we’ve only been talking about constraining SO2/sulphates so far.

So what about all the other chemicals not tracked? The more exotic compounds that the IPCC has in their range of forcings for sure, but then you find out there are some not in there? Like did you know microplastics, which now can be found in air samples, aren’t considered at scale for their possible heating or cooling properties? How preposterous is that? They’re now in all our air samples, but not enough in our air for aerosol calculation? No, it just hasn’t been done.

And what about the chemicals that leak into the air that shouldn’t (like air conditioning gases), or build up where they shouldn’t (like those suspended over heat domes), or don’t clear quickly? What about the compounds that form when chemicals react with heat or water in the air? I rarely see those modelled, and even when we talk about EU COMPOUNDS (in chemicals section) they don’t tend bother tackling air combinations.

(note, there’s also a connection between aerosols and cloud feedbacks. We’ve seen signs of this already just in the IPCC and James Hansen examples we’ve used, but please go read more in the atmosphere section. We’ll talk about the cloud feedback for heat separately, but when it comes to odd chemicals and clouds…there’s not a ton of work. So this will have to be an unknown unknown.)

And all of this has just been man-made aerosols. What about natural ones - fire and volcanoes especially?

76.3 Tg of carbon dioxide was one measurement of the Canada fires of 2023, but that was just the carbon. Assessing the effects of the actual aerosol dispersion from smoke is nightmarish, and I won’t pretend to tell you what it’s definite effects were, but work with me here:

If that fire year was the greatest yet recorded, and aerosol effect correspondingly large, what interplay do you think it had with the 2023 ‘heating’ pulse? The articles I’ve found all suggest the effects of those black soot particles were minimal and transitory, but I remain unconvinced given that the area under effect was about as large as the SO2 shipping fuels were. I suppose it’s possible that again, positive and negative forcings from such an event ‘mostly’ evened out, but do we know? Isn’t it odd that we just assume 5x magnitude fire year has no more effect on the air than a normal fire year?

Black carbon falling on ice may be a feedback itself, but here at least I see no evidence that ice loss that year was particularly bad. Did we get lucky?

Food

So, let’s get into food for a moment. Because if climate change and pollution are visibly linked, climate change and food should be just as simple no? Heat goes up, the crop either likes it or doesn’t, and we get a different yield.

It is, I think, worse than that.

Let’s start with a story – down the road from my ruralish home, about 200 yards away, is a large blueberry farm. They do very good work here and make some very delicious blueberries, and as you walk down the road you can get within a few feet of the bushes as the (super friendly) undocumented workers toil day after day to make the crops perfect.

The thousands of plants are usually placed in long rows that are labelled by variety, and from the road you can clearly see which lanes are marked as ‘organic’ or not. The workers spray the nonorganic crops regularly, and sometimes the smell of their compounds (whatever they are) reach my house for a few hours.

What’s of interest in this story is that the blueberries labelled as ‘organic’ are about five feet away from the other ones as they get their weekly spray.

Along the same line, just a bit further down this country road we’ve discussed, and still right there on the border of the berry fields, is the local state highway. I’ve counted the traffic on this road and on a slow day there are at least 4 cars per minute, and on the weekends usually dozens.

So yes, not only are the organic berries getting some amount of spray, but they are maybe 15 feet away from constant traffic? Sometimes there will be a spindly hedge between them and the cars, but given I can smell diesel exhaust at my home regularly, hedges likely aren’t helping.

Please understand I am not disparaging the berry farm. It is well regarded, consistently wins awards and the people who run it are lovely.

And yet every organic berry they grow just has *less* pollution and artificial chemical exposure than the rest. Not none, just less. And perhaps even more tire/car exhaust exposure.

Rising Hunger

Historically food and foreign aid programs have been remarkably successful. It’s often a bit mind-numbing as an individual to hear about them for year after year, decade after decade but it’s absolutely verifiable that worldwide food insecurity was on a steady decline from the 1950s til at least 2008. There is some definite noise in the 2010s, food insecurity rising in some first world nations for example (particularly the UK & USA), but even then mostly rises. Then COVID.

It's easy to blame many changes in hunger on the pandemic and what it did to supply chains, and maybe perhaps the food will begin to flow back into nations again soon. But so far from 2020 to 2025, food availability has fallen in a sharp series of steps, one after another. Not just COVID, not just the war in Ukraine and sudden changes in sellers/markets/costs there, but also the war in Sudan, in Myanmar, in Gaza. Suddenly nations are leaving the African congress and droughts of not just a season, but of multi-years have started to appear (Africa, Australia and Central America all). Multiple hurricanes hit Madagascar through to Malawi year after year (23/24). And then in 2025 the US threatens food aid overseas, reverses course, reverses again, and Middle East war flares to even more nations.

I’ve found it hard to pinpoint when famine first started its return.

Authentically it might not ever have left, despite the media narrative – it seems we don’t really care about each other enough as humans to exhaustively research and intervene in starvation, let alone to categorize accurately. There have been well-documented past famines and food aid has allowed many citizens worldwide in this situation to take assistance for a few years, stabilize their lives, and then not need that aid again. There has never been a long 30 years worldwide of constant ‘we feed the same people year after year in the same place’ scenario that I can find. Hunger has never gone away true, but famine did not seem to ‘linger’ anywhere outside of active warzones.

Then the Congo, the whole of southern Africa’s droughts, Venezuela, Cuba. Added of course to the new wars in Yemen, Gaza, Sudan, Tigray, Myanmar. The world report suggested 581 million people in malnutrition in 2019, but 733 million in 2023.

Famine records are harder to quantify, but of interest in 2024 famine was guessed at 1.1 million individuals (not including Gaza). This is a historical high for the last decade, and has been increasing every year since 2020, and that’s using ‘official’ UN figures. In reality, as normal, a full synthesis is entirely resisted.

For example, the whole of Gaza is 1-2 million people and has at points been in starvation to the point of infant mortality, but to label them as famine is against Israel apparently? Likewise, in Sudan 25 million people are being listed as in ‘active starvation.’ Is active starvation not a famine?

What’s missing apparently is active data verification, and UN institutional ‘green light.’ If we can’t prove someone is dying due to very specific criteria, then we don’t label them as such, and definitely not if there isn’t political will to do so.

This is bizarre to me, and the best sense I can make of it is that we have a conservative bias against declaring too many people dying? Someone must not want to hear about that, or want it said. God forbid we call out someone dying from food loss the wrong word, we have to be EXACT people! I find that utter bullshit – we should not allow millions to starve while quibbling over labels, and yet even cursory examination shows we do.

A responsible species should know if the amount of people dying from lack of food is increasing year over year. Not hungry or food insecure, but literally without enough food to maintain survival.

And yet we can’t do this – does that ever nibble at you in the night?

Inflation has a strong role to play here, and it’s interesting to me how persistent food inflation in particular has become. Many nations have at points seemed to be ‘through’ it, to the point some central banks are cutting rates, only for food to suddenly creep again a few points. It seems a dead issue to one nation and then you hear that in Turkey it’s back up. No wait, it’s been six months and it’s down again!

Then why are cocoa prices worldwide still at all-time records? Why is gold above 3300/ounce (again a record)?

Crop Failures/prices/inflation

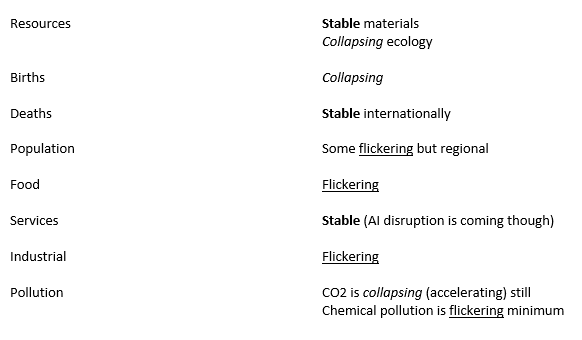

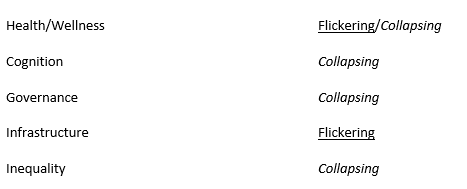

To my eyes today’s inflation never really leaving looks a lot a system flickering and failing to return to normality. Inflation can’t disappear because rather than societal causes alone, it’s a reflection of physical realities affecting ever larger areas, and for longer. Market stresses beyond normal (often 30 or 40% yoy, or much more) show capacity fading and price being used to try to buy equilibrium.

I watch wheat and soybean and rice and corn production very closely, and in general they have been starkly ‘stablish’. Stablish being big fluctuations in some places (China buying tons of soybeans one year, stocking up for a few more, then buying little only to suddenly buy again. Likewise, rice shortages in Japan that cause the national stockpile to be opened, but availability to never drop at scale) but overall worldwide production has been mostly sufficient. What is interesting is that worldwide production isn’t GROWING very much, and most acreage/yield numbers are going down, but not precipitously. In 2024 we did however have simultaneous breadbasket droughts in China, the US and Europe – something that’s never occurred previously. A bad coincidence? I doubt it, but also not enough disruption yet to truly be a disaster.

So for the main food crops of the world we might not even label them as ‘at risk/flickering’, ie, nobody is even down 10 or 15% of capacity yet. There is going to be a shock to these crops soon sure, and we’ll get into why, but it hasn’t happened *quite* yet and won’t in 2025. I’d call 2026 likely safeish as well.

See? We don’t just focus on the negative. We’re keeping our eyes on lots of systems, and using the stable ones to help us figure out the ones misbehaving.

Because while the ‘primary crops’ are doing OK, something else is happening elsewhere.

Cocoa, coffee, citrus, tea, potatoes, even beef and eggs and milk and butter have all experience >50% yoy rises at some point in international markets over the last 5 years. Some of these products have bounced back to ‘normal’ worldwide in that time, or at least regionally, and others have not. Coffee and cocoa in particular seem to be permanently elevated now, and we’re on the fifth straight year of warnings of supply for both. This means not just that supply has tightened but that production is no longer sufficient for demand – or to put another way, they’re in active collapse.

Salmon is much the same way, spotty production and some big fishery die offs, and given what we’re seeing in algae blooms already I’d wager that within 2 years at most there will be a mass poisoning as sicker and sicker fish are considered ‘OK’ to use. Because there’s nothing else.

BTW isn’t it interesting that if you were modelling the collapse of a food network, the first disruptions you’d likely see are to non-main crops, luxuries and crops grown only in small regions/etc, surging in price and availability at times, with some returning to baseline and others not? The only step after that is when the main crops go.

Depletion of nutrients in food

Measuring potential nutrient loss in our food supply over time is a fraught enterprise. Any gardener will tell you how unpredictable vegetables can be, and how different they can taste year to year. Factory plants are easier, but even then a small difference in varieties can lead to big confusion in nutrient measurement as different crops congregate different nutrients at different times dependent on different fertilizers. And as one good Indian study suggests (food/drop in nutritional quality in food) even the CO2 content of the air may be shifting how the same plant species perform in the same location.

We also have another study (biosphere/microplastics hinder photosynthesis) that suggest mircoplastics are altering plants too.

But what’s really interesting to me, is fusing the ideas! Think about it: CO2 and microplastics are both going to be everywhere at the same time, and now they might both be shrinking and inhibiting plants?

Oh hey wait. Less nutritious + less yield = less ROI. It looks like we have decreasing EROI in another place!

There is a lot to go into with soil nutrient loss, and I feel one becomes lost in detail there quickly. I quite consider it sufficient to point out that (more plant production) = (more loss from the soil) = (compounding loss over time), especially in soil we remove more nutrients from than we add. We live on a finite earth and we do not generally feed our soil EXCEPT to feed our plants. Anyone who has tried to regrow trees knows this – the soil is absolutely bare to start.

Hell, even human graveyards (a traditional source of nutrients in the animal world) are made pristinely free of other life.

I do have at least one other good observation with soil nutrients though.

Nitrogen in solid state in the soil primarily comes from nitrogen fixating bacteria, and artificially from fertilizer. Luckily with soil there’s a unique opportunity to consider a pollutant almost entirely on its own. In ground or aquifer water, we have a chance to study a single pollutant as nitrates generally only have one cause at scale underground and that’s ammonia fertilizer.

So what do we see with our (for once) mostly isolated sampling?

The picture isn’t pretty, but as it turns out the majority of aquifers in the US have some level of nitrate penetration.

And wouldn’t you know it? Nitrates are a poison, and a carcinogen, and many municipalities in the US don’t screen for it, don’t filter it, or don’t update their testing procedures every few years. This means the area of contamination is growing of course, and concentrations generally rising. As an example Illinois has gone from an average of 3.25 mg/L in city drinking water to 4.5 mg/L inside of 14 years. This a level considered safe for drinking by the way, which is capped at < 10 mg/L. And despite some studies that suggest NO safe level of nitrate content, at least according to cancer mortality risks (HR: 1.61, 95% CI: 1.07–2.43 per 10-fold increase and HR: 1.61, 95% CI: 1.08–2.42 for detection) over just 13 years, 20 to 39 year olds (so, young!).

And we can’t ever stop fertilizing can we? Not with tractor farming. So now most agricultural soil is receiving artificial feast-or-famine bursts that both transform the surface soil microbiome as well as introduce accumulating poison into the deeper ground water (and we’re not even taking into account topsoil loss). And since we’re on a finite planet, where does that lead? Some estimates are 40 – 60% of Chinese land is contaminated with fertilizer to the point of non-use. What do we think of this?

Is there a fast solution to the problem coming soon, or do we ‘run out’ of usable soil at some point? I make no claims as to ‘when’ here, but it’s interesting to note that it’s a conservative bias example – talked about lots but never assessed with full certainty.

Obesity

I mention obesity purely for one interesting detail –semaglutide. Here’s the situation: Food calorie density increases > people end up fatter because calories are more common > fatness progresses until type 2 diabetes incidence rises >10% of the population reaches this state in the US > we introduce a designed medication for obesity (to fight it, not necessarily stop it everyone though)

We have invented a problem (artificial nutrient density) and then instead of altering that issue at scale, we have found an artificial mechanism to deal with it. Will this encourage more overeating do you think? Less pressure on companies and governments to address the food density changes? Will there be other side effects from the use of this medication, or will we simply dial the formula in until we reach perfection?

Given the sale of the drug we are clearly proceeding forward on a path apparently unafraid (at scale) of any consequences.

Professionally I know enough about our medications that there will be definite side effects for some people. I also bet these side effects will be LESS than diabetes. So it IS a good drug. But on a societal level, why trade one new unknown for another, when a solution like ‘traditional foods’ was a known quantity? It smacks of an assumption of safety to me, of ‘the risk of 10% of a society on a drug’ being assessed as inherently low.

Of bias.

On Cherry-picking

There’s a lot of doom and gloom in this document and an immediate criticism I can see coming up is that I’ve ‘selected’ these crises. That the documents and the items we’re talking about, and the way we’re talking about them, might be intentional to create a dark picture.

Am I ignoring good events? Is sea ice expanding somewhere, or lots of places, and it’s just this ONE study saying that it’s falling?

I have two rebuttals to this – well, not rebuttals just gentle additions.

The first is please notice that in all instances we’re using peer-reviewed sources, government information, firsthand accounts, etc. Whenever possible we’re using multiple sources as well, so if there’s data here you don’t agree with, I would say you likely need to go ‘further up the tree’ so to speak, to find all the cherries. And given how many studies there are here, that’s a whole of bias in the system already no? As we predicted.

But the second addition is even more a burden.

Let’s imagine for a moment that you are right, and that I am picking the worst studies possible for this picture we’re building. My response is….would that matter? Have you considered that if this is mostly bullshit, there is a LOT of bullshit? Or that all these studies likely can’t be wrong? What if the AMOC really is down 20% (but no more), we’re at 1.5C now (2025), and some slight amount of Antarctica subsea permafrost is firing, but everything else is purely wrong?

Those 3 things are just observations and well, aren’t those 3 world-shattering events on their own? And what would their combination be? All the governments in the world could be headed toward peace and debt levels forgiven, but we’ve got no ice now. Likewise, the ice might be growing, but what if the micro plastic accumulations are still true?

On a systems level this is my response to any accusation of cherry-picking. I don’t mean to, but if I am, it might not matter. If 80% of things are fine, I’m still showing 20% that aren’t. And in a complex system like say the body it doesn’t matter if the kidneys are regenerating, a new heart has been transplanted, and a pedicurist is on her way – not when the brain is dead.

And I’ve got plenty of studies and measurements pointing out there may be more than just a few disrupted readings.

If I’m picking cherries here, we need to account for why there are so many cherries, and what happens if just a few of them really are true. And please, go apply the heuristics for yourself and ask, do they fit? Does it explain?

The biosphere

We often hear the biosphere is often too depressing to look at sharply, which is of interest to me. Isn’t that a general argument I have been making - we allow our biases to infect our reasoning to such a degree that there are subjects and thoughts we avoid?

(biosphere/etymologists thinking too conservatively)

This article is dear to my heart because it immediately illustrates my second principle so well – the etymologists first acknowledge that their estimates were far too conservative (1/2% loss per year initially, vs possibly 5% a year upon examination) as well as an acknowledgement of WHY it was so hard to see. They didn’t want to. Repeated observations were hurting the scientists, their empathy, their very history. And yet I might assert that to love a thing, we have to get our hands dirty sometimes.

So, yes, human activity is killing most of the life on the planet and doing it faster than has been synthesized into a whole.

As an example, the WWF estimates 69% of animal life has vanished since 1970 (they use a compounded rate of loss, but it’ll do for our purposes – and no one else has a better estimate, I’ve looked), with most of the loss ‘back loaded’ ie in the most recent years. Or to put another way, more of the population has disappeared recently in a description of exponential yet again. BTW, this figure is worse even than it seems. With animal populations constant loss isn’t really possible. Instead for most species after a certain threshold of individuals are lost the entire clade will disappear. And as animals mostly live in regional clades, this means when the lions in Zambia get to a low enough population there are no more lions. And then the lion in South Africa can go through the same thing. So not a steady rate of loss, but a series of sharp steps down, one by one.

That will be the next 10 years, using the WWF number. 2% loss/year x 10 = well, not many lions left. And by around 2040 as well, a year we’ll keep coming back to.

And worse, the population drops are showing up in protected preserves as much as the wild.

Even cultivated animal species keep crashing, and not just from pandemics. Bees particularly are crashing in multi-year patterns and in an interesting twist, we still don’t know why. For a time, the suspect with bees was ‘colony collapse’ syndrome, an unknown effect taking out entire regional hives, and some work was done to try match the syndrome to parasites, infection, or neonicotinoids and glyphosate but at last we’ve moved onto admitting general ignorance. Tellingly attempts to isolate bee colonies, to remove toxic exposures, or to (like on kangaroo island) completely isolate bee populations have all failed to protect numbers. Almost everywhere bees are dying en masse, and many food industries cannot keep up their replacement. Bee rentals have exploded in price.

(BTW, if my characterization of the collapse of animal populations seems wrong to you, here’s an exercise – please go find a populous animal or plant species that have maintained a growth surge worldwide in the last five years. I wasn’t able to find any. Think about that. A whole planet, and while there are some regional surges, or 1 to 2 ‘explosive’ years, the moment we look at the whole of a species across multiple regions I can’t find anybody surging at scale. No niche winners, no new universal expansions, no foodweb role. Unfortunately, I think for any species to do a real expansion, it needs an ecosystem there and the truth is all major ecosystems are in decline now. We have no new winners because the general substrate of life itself is failing. But please, go look. And please, weigh how many examples you find versus the amount you find in decline.)

Avian flu

The current strain of influenza is unprecedented in scope, crossing the entire world, with animal’s deaths estimated in the billions. Please do let that sink in – it’s doubtful modern science has ever seen a pandemic of the severity of this 2+ year old illness and given our inability to assess let alone contain the pathogen (look at the milk and egg prices in the US throughout 2023 and beyond – same with beef and pork prices worldwide) in cultivated sources, I do not hold high hopes for even a COVID level of response should a human mutation occur.

Somehow in only 4 years (and with COVID still very much present) response capacity has degraded. International cooperation at scale on this crisis has been effectively nonexistent, perhaps not surprising for an animal crisis, but even internal operations for the disease haven’t worked. At best domestic flocks are culled or isolated, and yet neighboring farms are left to test/inoculate/prepare entirely on their own. In the US meat production companies have had to take the lead in what should be a public health operation – an insane proposition, like individual hospitals trying to contain city-wide measles outbreaks.

I helped create COVID responses from month 1 of the last pandemic, pulling out dusty pandemic plans from previous decades, and my assessment of avian flu preparations is that we don’t even hit that mark. Public health in the US is currently less informed, less organized, less cohesive and less interested than we were BEFORE a world-wide pandemic.

And that was before the FDA cuts of 2025. Avian flu had record spread in both chicken farms and cow herds throughout the first half of 2025, and yet still the cuts came. One hopes that there is a better plan than not worrying, and that the cuts don’t effect pandemic preparation, but the heuristic tells me to doubt.

Biosphere theory in general

Finally on this topic, please don’t be surprised by the mammoth drops in animal numbers we see in the datapoints or in my musings. Or in the talk of catastrophes beyond just the human world. It’s not just the cutting of old growth forests (7% of earth’s land surface left), or factory farming, or foie gras, or blinding pigs to breed more, that has defined the human treatment of animals, it’s also our disdain for tracking their numbers. Or preserving specimens before a species goes extinct.

In point of fact out disdain of other life may just be part of human character. Another conservative bias we don’t think about and don’t imagine in ourselves.

If you’ve ever attended Australian school, you’ve likely learnt of Australia 40,000 years ago. Of kinds of animals and trees that haven’t ever been seen in the modern world. Wombats the size of cars, 200 ft tall gum trees, vast temperate forests with birds bigger than humans - all burnt away by early humans. The taught curriculum is that these humans (not any other species, just humans) may have been fire-hunters, and somewhere in their history they let the practice get out of hand. The result was an entire continent scarred by flame and now missing most of its topsoil. A recently living land left dead and burnt and dried and just vanished into the wind.

There are some who dispute this version of events of course, and they could very well be right. More interesting to me though is that the story is passed around Australia still, implying some large amount of people that believe humanity capable of this sort of thing. Remember that with everything else we talk about; it’s possible we’ve done this before.

And what I like about this story is that when I speak of it to non-Australians, most people generally accept it quickly. It’s like talking about 2100 with folks. Why yes we might be in a lot of trouble by then, especially because there will be so much trash. Or because most of the animals might be dead. And of course the air will be worse, because we pollute too much.

These are all, maybe surprisingly, common beliefs. So there is the possibility in many humans that we ourselves could potentially be a problem someday, even if it’s not now. Even if we don’t all agree on climate change or populism, most folks do agree deforestation and chemical pollution are being caused by us. It’s just rare that those things are a danger now. A worry certainly, but there’s no talk of a new Australian outback tomorrow.

Which I kind of find to be…ass-backwards?

Think about it. Everyone accepts that humanity can be short-sighted monsters that ravage the planet – it seems to almost be accepted fact. It’s just that that most folks (and governments today, as an example) assert the consequences for our actions can be unfurling right now. It takes time we say, or they aren’t extinct yet (as if extinction debt doesn’t exist). Yes the human race is short-sighted, but the Amazon still has time.

To which I say, but If you’re short-sighted doesn’t that mean you don’t recognize when something is happening? Isn’t that the definition of short-sighted, that you can’t tell how far away a thing is?

Just something to consider.

Oceans

Unfortunately I have no real hope for sea life even beyond another decade or two, so I will generally leave it out of our considerations. We have studies showing that even plankton populations are in mammoth shifts right now, with 2% or more changes a year (what might be called a collapse might some). This is even more deeply disturbing when one considers that sea life is responsible for the majority of earth’s oxygen, but that doesn’t appear to be a problem on the same scale as others. I hope I’m not wrong on that.

The first immediate concern in the oceans is surface temperatures, especially figures appearing in 2023. In March of that year we saw a burst of heat that was quickly worldwide and wholly unprecedented as far as I can tell. By May of that year, .25C average anomalies had spread almost across the entire earth, with a few spots being much more. The nature of this heat has escaped any complete analysis in my estimation – not just why was it so hot, but why was it so widespread and synchronized? Hansen’s explanations come closest with aerosols, and yet I cannot help but think his is still an insufficient model. Consider – the heat is EVERYWHERE in 2023, while the EEI shows up in the North Pacific yes, and even in the North Atlantic, and yet the whole planet’s EEI doesn’t change everywhere at once. Below 40S, in the southern hemisphere, there are very little aerosols and yet the heat shows up here too at about the same time.

When I try to imagine something that can heat all the world’s oceans within a few months all I can imagine is the sun, and the ocean currents themselves. We did start entering the solar maximum phase in 2023, and it has been a prediction-defying strong maximum, but a .25C anomaly would be completely outside of any modelling, and doesn’t pass a smell test. That much sunlight would be noticeable to your naked eye at the scale necessary. So yes the maximum could be a (small) component, but not the bulk. So – ocean currents? Is that possible? Could a nearly worldwide shift have occurred in ocean behavior in the first part of 2023? This explanation fails for me too – as much as the oceans are all connected, and the sea anomaly shows up in Antarctica waters (all time ocean high for March reached in 2023 off Elephant Island) the same time as the North Pacific, sea currents aren’t suspected to be that uniform or that connected. Unless of course we don’t understand mixing (or heck, even ocean currents) as much as we think?

Or what if 2023 wasn’t one cause? What if what we saw starting in the oceans wasn’t a systems change, or rather just the system changing? What looks like a ‘jump in 2023’ isn’t a jump at all, but a system threshold, with normal activity giving way to new momentum? It is Hansen’s aerosols there yes, and that’s a jump, but rather than one large single jump, the increases could be the unmasking of aerosols combined with weakening currents combined with EEI mismeasurement combined with marine heatwaves that have been spreading heat much further and much longer than we were thinking at the time. And what if instead of ‘seeing’ a sudden change in the ocean SST in 2023, we noticed that the deep oceans had been changing in 2009, and the arctic ice changing in 2000, and the EEI changing in 2006. And wouldn’t you know it, the trajectory of each of these is up, and has been for decades, and we simply need to learn to layer them together.

In this picture of 2023, ENSO and tonga and SO2 removal all hit at around the same times, and any resulting sum of heat overwhelms natural variability. In this picture SO2 probably did show up in 2021/22, but it wasn’t enough yet to overcome ‘normal’ behavior. But then when other forcings are added to it, we get a ‘leap’. In this (purely theoretical) situation, we do get another interesting possibility btw – what if naturally ‘cool’ periods right now have a strong heat forcing under them, and so only appear stable? And hot periods? That’s just neutral periods + forcing. Maybe we’re not having a ‘hot’ event at all, just so much distributed heating that everything now looks hot.

Regional oceans have some strange readings along these lines. In 2024 we saw surface temperatures in the Atlantic hurricane MDR reach quite unprecedented levels. But unsurprisingly some of the fastest accelerated hurricanes ever resulted, and quite ‘ahead of schedule.’ And with huge damage totals.

In 2024 and 2025 we also saw ocean heatwaves combining with drought on land to create the Kangaroo Island algae blooms that continues to kill so much sea life around South Australia.

With events like this ongoing, I think it’s safe to say that sea temps alone will be able to give us on land a number of ‘black swan’ events, and that’s before typical Earth numbers melt away into our next ‘other world’ state.

On Earth, back in the Jurassic and Cretaceous there were several large storm events that killed many migrating hadrosaurs. Hurricanes large enough to leave fossilized sand waves at the bottom of the ocean and hail stones weighty enough to crack open a triceratops’ rather thick skull all occurred. Presumably Earth’s gravity conditions were the same then, so the only major drivers were talking about would be heat and atmosphere differences, and we’re heading in that vector now. It makes me wonder at what point is having an extra 1.3w/m2 going directly into sea water going to have effects we did not anticipate? How long is the road from the modern world back to that one? Is there a reason to assume it’s far away? I like these questions because it helps us ask, when should we use the precautionary principle? The Jurassic is VERY far away from today, and yet is it so far away we should forget that it was the same planet?

One dynamic that is crazy hard to model: the absorptive balance between the air and the ocean. In 2023 when the oceans jumped .25C, the air temps did not jump nearly as much (proportionately to heating potential that is). Yes 2024 was the hottest year on the surface, but it wasn’t even close to how much hotter the oceans remained. I have several studies on ocean inertia waiting for that you that describe the possibility that more energy is making its way into the oceans now than usual, something like 91% bypassing the air instead of a more typical 89%. That shift of 2% is mammoth, and also not particularly well understood. When did this shift happen precisely? What is the dynamic behind it? Will it increase further? Or will it possibly decrease, in which case air could leap even more than .25C given the difference in each medium. Whatever these mechanisms are at play here feel a lot like ‘jostling about’ to me, an interplay of liquid physics dynamics that mean different minute threshholds of energy transfer cause big shifts. Like increases in saltiness changing electrical potential. I do not know this is the case, but I also don’t think we should trust this ratio as being stable – we don’t know the cause and the dynamics at play might be wickedly complicated, shifting from resistant to conductive back and forth or getting more extreme. And hey, they just changed on us right? Why not more?

Hydrates + subsea permafrost + pluming

You’ll have noticed by now I don’t use a lot of numbers in this document (at least not compared to institutional pieces), and a lot of loose descriptors like ‘larger’, ‘faster’, ‘worse’. This is, believe it or not, intentional. This whole document is about how there might be more errors out there than we think, and a good place for errors to hide is numbers (‘safe’ levels of nitrates, EEI measurement, aerosol forcing, the year something ‘is supposed to’ happen). So I like to stay away from solid figures and even when I give you numbers, know I hold them ‘lightly’. IE, I expect any number I use to be wrong. This is why I like simple words like smaller, or slower, or more. Words like this describe relationships between two things, and I like knowing that space between them a lot more than I like pretending I know precisely the position of both items. Why do I mention this? Well at one point I considered rating the dangers we face (the size of our potential errors), before I realized how silly that is. I could list micro plastics as the 15th least likely danger I talk about (it’s not) and they could STILL kill us, yes?

With all that being said, here’s a danger that’s very large. And of course we rated it as very unlikely.

And a warning, trying to research methane hydrates/subsea permafrost/and the possibility of their status change is simply maddening in the current world. Let me demonstrate why:

No one studies methane hydrates at depth, over time, in situ. What few studies have been done concerning them seem to use laboratory conditions, how much direct air heat it takes to disassociate a hydrate, or consist of theoretical dynamics studies of Saturn’s moon Titan. No one can say exactly how a hydrate works here on Earth because of how varied their presentation, and every time a theorist begins to work on them the same refrains come up. But hydrates are at PRESSURE, is the call! And pressure will protect them!

And yet one can never find submarine data down there to match conditions either…

It is much worse than this though.

Sometime in 2013, while trying to understand dynamics at Earth’s poles, I came across Shakhova’s 2010 interview about the possibility of 50Gt methane releases from subsea permafrost in the East Siberian Arctic Shelf. Curious, I looked her up, learnt about the Siberian Traps and about how few expeditions there were to that area, and how this scientist performed studies there on site, on the water, for months, gathering datasets that are still used often elsewhere. I even learnt that her team filmed some of the plumes that had begun to appear throughout the region.

And then I immediately discovered that this scientist’s warnings were…somehow controversial? Dismissed? That nothing had come from that interview by an at least still referenced scientist working with direct observations? I had immediate thoughts. If this person (who I don’t know, maybe she’s awful) is untrustworthy, why is her data being used? If she’s wrong, where are the other measurements or experts from that same regional area of study to refute her? Wait…there AREN’T any other scientists who go to the ESAS and look? She’s it, she (and her team of course) are the experts? So why is that interview discounted? Who else is doing observations in that spot?

It’s even more maddening when one discovers a paleo record that quite supports her claims, namely that the Siberian traps and the arctic shelf offshore have been putting out a lightshow of concentrated methane and hydrocarbons since before the Triassic. Perhaps this won’t shock you, but that very region is in fact the single LARGEST, CONFIRMED region for methane build up on the planet – riddled with hundred-kilometer-long rock formations that descend into shallow water, that are often capped by ice, and where deep lava tubes can bring pyrogenic methane upwards to form giant pockets. This region is a likely source of the P/T extinction event even, responsible for an interplay of volcanism, coal and methane that reshaped the entire planet at least once before.

And so here we have a scientist with repeated direct observation of a zone, who’s data is still in use, but who’s conclusions are suspect because…why? Why is a 50Gt release so suspect?

The arctic was changing even before 2010, and the years after have only made it more obvious.

We have lost Marc Cornellisen, Phillip de Roo, and Konrad Steffen to a changing arctic. These were experienced scientists literally studying thinning ice and cryosphere changes, trying to identify and predict a problem, going on site to measure significance, and then losing their lives. That’s actual death right there, so why is it still so hard to imagine a world changing? Or that this changes might be…significant in nature? How easy is it to stay in a nice office, or a warm living room, and deny the hard work of scientists locked in ships or camping on ice?

But we’re still not done here, and it gets worse. Because in 2025 we still have a war with Russia ongoing, and thus an isolation of data. And so as of this date, Shakhova and her team’s last observations remain the MOST RECENT expedition to the entire ESAS. And likely will be the same for the expected future. Dismissal of Shakhova now smacks of short term thinking and simple stupidity. Especially when arctic plumes continue to grow and now show up in Antarctica waters as well.

Atmosphere flux readings from Canada and Greenland and the Nordic countries are all mostly stable (though elevated), and yet I am not comforted being blind in Russia. Methane sources of some kind are firing at both poles, and now we can only realistically quibble over the magnitude, or source, and not whether are even happening or growing in size (they are). And all that methane must go somewhere, no? Given Shakhova told the possible upper end of where this could go and the fuse is ALREADY lit, I would say we pay attention.

Quick math from Shakhova is 50Gt from the Arctic. The Spanish expedition has said 24Gt from their site in Antarctica. Should either reservoir turn over fast (like the methane sinkholes showing up in land permafrost), they could quickly double current global warming. Will they? I don’t know, but we had a warning about this.

And btw, these sources are not planetary methane hydrates either, but merely (likely) shallow water subsea permafrost deposits at the poles.

Planetary methane sources are a lot worse.

If Arctic methane is almost always shallow, and Antarctica mostly shallow, the rest of the earth’s hydrates are generally deep water. >500m depth has always been the koan repeated, and they are stable due to ocean water that takes decades to shift (if at all) and massive pressure. And so with these firm forces in place, even today clathrate gun theories are solidly in the realm of conspiracy theorists and Guy McPherson. It doesn’t matter how many plumes there are at the poles, and it doesn’t matter if surface waters have jumped more than modeled, general discourse treats methane hydrates as a doomsday scenario of the paranoid.

Well, they are at least very much doomsday, so let’s get into it and see.

(oceans/bottom marine heatwaves, gas seeps and hydrates, bottom marine shelf heatwaves – do please notice all 3 studies have different authors, and from different institutions. We’re not using any one or even two data points here, we’re going broad)

The first correction we need to make is that deep oceans are likely neither static nor insulated. Not only do we have diverse evidence of ocean heatwaves at shelf or ‘shallow’ depths such as 250m, but also of bottom heatwaves at depths of a kilometer down. It appears that marine water columns shift more than assumed, and that at least some currents transfer heat faster than initially thought. Neither are such events short, and several degree C increases have been observed lasting several months in a repeated behavior. This length is especially relevant as often hydrate stability is defined in terms of something like resistant to heat for xx amount of time. Well we can move past such metrics already, and now we simply need to assess how deep and how long for each deposit.

Wearisomely surface warming doesn’t reflect deep warming either, so we can completely not know when a bottom heatwave is taking place. We appear to have been missing them for decades even. In retrospect analysis 2 general ocean-wide system shifts seem to show up for heatwaves, one in 2009, and another (larger) in 2019. With these we now have evidence of hydrate stability zones dropping something like >50m/year on shelf hydrates. This won’t be full unwinding yet certainly, but nonetheless these are zone of potential activity that will migrate toward movement/instability in the ‘near’ future. Deeper hydrates are supposedly more safe, but I find this repeated claim insufficient for confidence – my true guess is we simply are not looking at scale, and so ARE GUESSING WE’RE SAFE.

Unfortunately both shelf and general bottom heating are likely to be accelerating processes right along with all our other heat events, and will rise even faster with localized events (like heatwaves). In practice what this means is that there is the possibility of a ‘lens’ effect over a previously stable hydrate zone, creating the potential for extreme and sudden destabilization from concentrated forcing.

There’s a natural inclination to try to match methane hydrates to subsea permafrost, but I advise not to do it. In permafrost the methane is generally thought to have had less time to accumulate, and is under a lot less pressure. And btw the lensing potential over permafrost is probably even greater, with Arctic/Antarctica amplification putting the shallow water under a magnifying glass (another unanticipated reality that appears to suggest Shakhova’s theory of release is even MORE likely).

How do we know hydrates aren’t firing at scale now?

Currently the general physical theory is that should large amount of hydrates be firing at any time, we’d see the evidence in a burst of atmospheric methane. And indeed on one hand the atmospheric methane does appear to be growing. But on the scale of planetary methane releases? No. I’m not seeing it. What’s more worrisome though are theories that methane released deep enough down in the ocean NEVER make it to the surface, as ocean dynamics and biological reaction reduce the releases down to chemical components. But what’s the upper limit to this? Is there an amount of methane that could be released constantly and not appear anywhere in surface/air readings? Could a small leak be happening almost everywhere, and not show up unless you look for it? I’m not sure. It seems unlikely, but that’s the bias talking.

Instead let’s make a few observations, and work this through on a system level. First we should acknowledge that we don’t look at the oceans enough. We don’t actually go down there that is, let alone down there all over the place. Also, unfortunately, hydrates appear to be almost everywhere. Not just in the ocean’s deepest depths, but right under the ocean floor in lots of other places, and how large might those deposits be? Well they’re buried in the ground, underneath the sea so…we don’t know. And given the size of the oceans, hydrates right now could easily lose something like .005% a year worldwide, have it be turned quickly into CO2, and we wouldn’t be the wiser. Just another layer of our ‘stacked’ 2023 forcings for example. But IS that happening? And could worse releases actually be happening and being missed to?

Here’s where we humans come into play, in my thinking. Let’s list some things we’ve been wrong about: we thought the oceans didn’t heat up at depth, we thought it took a long time for them to heat up, and we thought any changes were well into our future. So when we look at that track record…suddenly ‘pressure will always keep hydrates safe’ seems a very thin last hope to me. So my thought here on hydrate destabilization is a very firm ‘we don’t fucking know.’ Large scale destabilization could be close, far away, never at all, or already happening.

But here’s the clincher to me – what would it look like right *before* deep sea hydrates somewhere started to destabilize at scale? We already said that small loss might be invisible, but surely before the deep sea goes some other deposits would? Well here we end up at subsea permafrost again, but that would likely fire first right? And not just a little, but big seeps, showing up more and more, hundreds of kilometers wide? Well that’s happening now.

And we’d also expect some marine heatwaves yes? Heat of a few C at least, for months at a time, sitting on top of the hydrates? Hmmm, that’s happening too isn’t? At least in some places.

Is there anything else? Any other warning signs we’d get? Maybe weakened or changing ocean currents? Well don’t worry, we’ve got those too.

All of this is happening right now. Do you start to see the problem with confidently asserting that 10,000Gt of CO2 equivalent of methane hydrates are all completely fine?

Ocean acidification

(ocean/Ocean_PH_graph)

It amuses me to no end that the appearance of ocean acidification matches so closely to atmospheric CO2. It makes sense!

So of course there’s probably more to it.

For whatever reason when I think about acids in the ocean, I begin to wonder about methane hydrate biodigestion. Follow me for a moment - Everyone says the methane from the hydrates gets eaten by the critters, and we don’t need to worry about right? The methane gets spread through the column, eaten or reduced into carbon, and the carbon will...go into the water? How is carbon in water exactly not what is happening with ocean acidification? Are we sure we know where all the acid in sea water is coming from?

At this point in the document you’re probably not surprised to learn that ocean acidification is the sort of problem that has been identified as potentially catastrophic and even labelled as a ‘planetary boundary’ by the Potsdam Institute. Luckily, at the beginning of 2025 they were quite sure that this boundary was at risk. But then of course I’ve now seen a study suggesting we might have passed that same ‘safe’ boundary condition five years ago, at least within >60% of ocean layers and zones. I’m not going to say one study proves Potsdam was in error, and in fairness mixing environments can be wickedly complicated to reduce, but wouldn’t it be ironic if another boundary was actually LONG past?

This really is a worrisome thing we should be tracking by the way. Results of such a passing (as measured by seawater with aragonite saturation state > 20% reduction) would mean the nonstop decline of calcium carbonate organisms – no need to wait until 2060 when it was previously predicted to finally hit the majority of the oceans.

As an aside, if confirmed this regime shift would actually make it 7/9 boundaries now ‘passed’ in the Potsdam Institute/etc global health check. My confidence in predicting coral functional extinction by 2030 grows.

Ocean ‘unknowns’

I have suspicions of forces at play in ocean dynamics that I have yet to see either good observation or theory one. One example is micro plastic pollution building and suspending in water columns – think microscopic layered trash, suspended at varying heights due to water density, forming layers and trapping heat/water/other matter above or below the ‘settled’ layers. Carbon or some pollutants might do this too, and I haven’t seen much information on a greenhouse effect in the oceans themselves. Seems a pity, given how big they are. Pollutants on the floor bed are (a bit) more studied, but how do they interact with methane hydrates I wonder? Could plastic or chemicals be abrading surfaces over time? Or strengthening those marine heatwaves? If so the effect will be everywhere, so even a subtle value might compound.

Similarly I wonder about hydrate fractionalization – we know now that warm waters are bathing hydrates at scale all over the planet, does this cause some amount of evaporation? Even if we think we’re far away from a heatwave breaking apart a deposit, I’d imagine there is some potential for ‘loss’ of some kind from surface exposure, especially with repeat events. How much? Does it matter? No idea, but we’re trusting on that sort of thing to be small and insignificant now.

Final comments on Ocean

I have gone looking for marine data, and it is hard to find. Authentically looking at the size of research on ocean matters versus the size of research on everything on land, and you quickly tell just how little we care about the waters. It’s obvious, we’re land based, right? But it’s just not true. We might be based on land, but the oceans are air, transport, food, and heat and humidity. They are the walls of our cradle, and it is a bad sign to me when data is regional or satellite at best, and deep water and bottom studies are as rare as they are. There is simply a lack of interest in the oceans, and an assumption that whatever is there can’t matter. Does this sound like a reasonable situation to you? The kind of scenario that should exist if we responsible, attentive members of the Earth system?

And if the situation was bad before, the defunding governments have gone through in the 2010s has only ramped up into the mid-2020s. At a time when the oceans are observationally changing the most and the fastest ever, we are cutting out more of our eyes. Why? I find this bizarre – the oceans are the most alien places we can access on earth and alien things can hurt us. And instead we are ignoring them and finding ourselves confused with how they behave.

An application of the heuristic

I didn’t come up with the heuristic to share with you. Or rather, I’ve had the heuristic for years, I just didn’t think to share or formalize it until I started to understand the real scale of the problem. Like you, at first I just found that it explained a few things here and there. Stupidly, I never took it further than that.

I can literally demonstrate this stupidity of mine to you.

(Atmosphere/ 23 whiteboard.jpeg)